Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States by James C. Scott

Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States by James C. Scott

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

There has long been a debate over the merits of the life of the "civilized" human being over that of the "noble savage," one that seemingly turned decisively in favor of the modern state as the European empires expanded over the last several centuries. As the Thomas Hobbes memorably stated in his description of the state of nature, “and the life of man, nasty, poor, brutish, and short.” But what if Hobbes was wrong? Perhaps if he had considered the lives of London slum dwellers and American slaves versus the hunters and gatherers who persisted in much of Africa and the Americas at the time, he might have reached a different conclusion. History, after all, is written by the victors.

Perhaps the concentration of power in urban centers with its attendant dependence on a restricted diet of monocultures, especially grain, its problems of sanitation, concentration of germs and parasites and susceptibility to epidemic disease, its submission to the tax gatherer, and its imposition of the round the clock drudgery of agriculture and industrial life, was not a material improvement for most people over the free ranging life of our ancestors. With its diseases and hardship, was civilization worth it? James Scott's Against the Grain, provocatively poses the question, even if it does not fully settle it.

Modern man has in effect been domesticated; we have lost the skills necessary to survive in the wild. There is an easy assumption that people living off the land were weaker and stupider than their urban and agricultural counterparts, and yet for much of the last several millennia, it was the poorly nourished and disease-ridden domestics who were weaker, less well nourished, and comparatively far overworked.

“Nomads, Christopher Beckwith has noted, were in general much better fed and led easier, longer lives than the inhabitants of the large agricultural states. There was a constant drain of peoples escaping from China to the realms of the eastern steppe, where they did not hesitate to proclaim the superiority of the nomad lifestyle.”

The assumption has also been that because people lived in the wild, they led a haphazard and unplanned existence. Anyone who has ever been even on a short camping trip, however, knows the importance of meticulous planning, and the supposition that the multifarious bounty of the land was less reliable than the laborious cultivation of single grains notably subject to crop failure may be misguided.

Scott argues, in contrast, that life outside the modern state was a rational and healthy choice for most of humanity for most of its existence. The rise of the modern state, with its bureaucracy, written records, monumental architecture, standing armies, and above all its tax collector is an aberration not a norm. The initial reasons for the adoption of the state form are not wholly clear in light of its obvious epidemiological disadvantages, its imposition of additional labor, its nutritional deficits, and its deprivation of freedom.

“There may well be, then, a great deal to be said on behalf of classical dark ages in terms of human well-being. Much of the dispersion that characterizes them is likely to be a flight from war, taxes, epidemics, crop failures, and conscription. As such, it may stanch the worst losses that arise from concentrated sedentism under state rule.”

Literacy, or rather initially numeracy, increased in states where it was necessary to track and inventory not only grain, but also people, who quickly became the nascent states' most valuable commodity, whether as citizens or slaves. Scott suggests that the rejection of literacy by people outside the state in favor of oral culture was part and parcel of a rejection of the state's assertion of control over its citizens through walls, taxes, and violence. Scott quotes one researcher as posing the question:

“[Why did] every distinctive community on the periphery reject the use of writing with so many archaeological cultures exposed to the complexity of southern Mesopotamia? One could argue that this rejection of complexity was a conscious act. What is the reason for it?

Perhaps, far from being less intellectually qualified to deal with complexity, the peripheral peoples were smart enough to avoid its oppressive command structures for at least another 500 years, when it was imposed upon them by military conquest. . . . In every instance the periphery initially rejected the adoption of complexity even after direct exposure to it . . . and, in doing so, avoided the cage of the state for another half millennium.”

When the infant states of Mesopotamia crumbled every few generations, as they regular did in the face of war, plague, famine, or political infighting, the reversion to life outside the state was not necessarily a disadvantage to their erstwhile citizens. So long as the option was available, a free life dispersed amidst abundance may often have been preferable to confinement behind the city walls.

“The abandonment of the state may, in such cases, be experienced as an emancipation. This is emphatically not to deny that life outside the state may often be characterized by predation and violence of other kinds, but rather to assert that we have no warrant for assuming that the abandonment of an urban center is, ipso facto, a descent into brutality and violence.”

Ironically, Scott points out that such defensive works as the Great Wall of China were actually constructed as much to keep citizens in as to keep "barbarians" out. The rise of the state itself was only possible with a confluence of systems designed to keep people under control in order to produce the grain surplus necessary to sustain a class of citizens not directly engaged in procuring or providing food. Only this kind of surplus made possible a specialization of labor, and the surplus was achieved by virtue of walls, taxes, armies, literacy, and slavery, which Scott argues is a foundation of the modern state throughout most of history.

(In that sense, the Confederacy may have been more than a throwback than an aberration. It is noteworthy, although often overlooked, that both Classical Greece and Rome were sustained by large slave populations. Moreover, even today, our modern civilization in dependent on exploitation of labor under conditions approaching slavery, whether it be Foxconn or Federal Prison Industries, and literal slavery is not extinct. As George Orwell pointedly remarked in his essay on Kipling, "We all live by robbing Asiatic coolies, and those of us who are ‘enlightened’ all maintain that those coolies ought to be set free; but our standard of living, and hence our ‘enlightenment’, demands that the robbery shall continue.")

For centuries after the rise of states, citizens and non-citizens of states lived in an uneasy equilibrium, with the latter far outnumbering the former. The concentrated wealth and manufactures of states were both a source of trade and of plunder for stateless "barbarians," whereas the "barbarians" provided transport and often protection upon which the states depended. State relationships with non-state peoples often took the form of a protection racket; states paid "barbarians" on their frontiers not only not to attack them but to protect them from other attackers. Rome paid generous subsidies in the form of "gifts" to the Huns and the Celts in return for nominal recognition of Roman suzerainty.

Scott does not deal extensively with the factors that ultimately tipped the balance in favor of the modern state, the near eradication of stateless peoples, and the "domestication" of virtually the entire human race, but he does suggest that the invention of gunpowder – which ended the advantages of cavalry – and the urban-incubated European epidemics which swept the New World were decisive factors in tipping the balance and ending the "golden age of the barbarians."

View all my reviews

Life's Regrets and a Lost World

An Artist of the Floating World by Kazuo Ishiguro

An Artist of the Floating World by Kazuo Ishiguro

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

An Artist of the Floating World evokes a lost world of artists' lives in the pre-War Japanese demi-monde against the rise of strident propaganda leading up to the catastrophe of the War. At one point, the narrator, Mr. Ono, a painter, describes his masters' geisha paintings as updating a classic 'Utamoro tradition' in order to "evoke a certain melancholy around his women, and throughout the years I studied with him, he experimented extensively with colours in an attempt to capture the feel of lantern light." Even as Ono turns his back on this "floating world" to create a "new Japan," the war consumes his old pleasure district, leaving only ashes, fertile ground for Japan's new Americanized business culture.

Against this backdrop, an Artist of the Floating World is a novel of guilt and remembrance, perception of self and perception of others, a brief journey in which Mr. Ono must confront the legacy of destruction he helped create and the passing away of the fragile aesthetic he once cherished.

View all my reviews

The Birth of the New World from the Unexpected Perspective of its First Arab Explorer

The Moor's Account by Laila Lalami

The Moor's Account by Laila Lalami

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

The fall of the tiny Moorish kingdom of Granada in 1492, marking the consummation of the Spanish reconquest and the division of the Iberian peninsula under Spanish and Portuguese rule, generated a ripple whose shock wave ultimately resounded throughout the world, not least in Spain's neighbor the Sultanate of Morocco. As the last remnants of the glittering kingdoms of El Andalus fled across the straits to North Africa, Ferdinand and Isabella were able to employ the fruits of victory in financing an obscure Genoan adventurer on a desperate voyage to the Indies. In one of history's greatest accidents, Christopher Columbus landed in the Americas, setting off a chain reaction of disease, conquest, and exploitation that swiftly overturned the established order in the New World to the unimaginable enrichment of the Spanish empire. The dazzling success of Cortes in Mexico spurred the Spanish nobleman Panfilo de Narvaez to mount an expedition to la Florida in the buoyant expectation of outdoing his predecessor on the shores of the vast unexplored North American continent. After all, there was every reason to believe that the untold riches of the New World had barely been tapped, and the unmatched superiority of the Spanish fleet at sea and the Spanish cavalry on land had allowed relatively small forces to melt all resistance from the Native Americans like wax in a blast furnace.

It is a commonplace of classical tragedy that the hero is brought low by hubris born of overconfidence in his great strength – whether it be Achilles rushing forward into battle, Odysseus taunting the Cyclops, or Oedipus slaying the king his father and marrying the queen his mother. This story of the Narvaez expedition melds a fast-paced adventure story with the arc of a Sophoclean drama. Abandoning its ships and plunging headlong into the swamps of Florida, the Narvaez expedition drives all resistance before it only to find itself stranded without either gold or food, and its dwindling number of survivors – ultimately only four – find themselves at the mercy of the very Indians they had hitherto so cavalierly murdered and tortured in their monomaniacal– but futile – search for gold. In the end, the only four survivors were three Spanish noblemen – one of whom, Cabeza de Vaca, wrote the definitive account of the ill-fated voyage – and a Moroccan slave known only by his Spanish diminutive – “Estebanico.”

In her richly imagined novel, Laila Lalami recreates the disastrous expedition from Estebanico's perspective, interspersing flashbacks to his upbringing in the Portuguese-dominated Moroccan city of Azzemour with a fast-paced narrative of hardship and danger as the desperate Spanish seek to cut their way out of the trap of their own making in what is now the Southeastern United States. Told from the perspective of a man gradually emerging from slavery in reliance upon the good will of the native tribes, the novel simultaneously offers an empathetic view both of the disastrous impact on native culture of the Spanish incursion and of the ruthless invaders undone by their lust for gold.

Lalami's deft narrative not only conveys a sense of the sixteenth century down to the very diction of the narrator but also creates an impression of scrupulous historical accuracy. In so doing, it provides a kaleidoscopic insight into the intersection of Arab, Spanish, and Native American cultures in the age of exploration from a refreshingly different point of view. Quite apart from being a page-turner, this novel offers a fascinating insight into the devastation of old civilizations and the birth of the modern age.

View all my reviews

Good-bye to All That

Great writers often seem to lead messy lives, and none more so than great memoirists, for tidy lives do not make great memoirs. While not as talented a poet, Robert Graves was every bit as batshit crazy as William Butler Yeats, with more cause, and as with Yeats, I have repeatedly fallen in and out of love with Graves over the decades. As Paul Fussell explains in his magisterial [book:The Great War and Modern Memory|154472] the only way to understand Graves' Good-bye to All That is as a mordant burlesque on the darkest of events. (A commonly cited example is Graves' story about making tea from machine gun coolant.) It may seem irreverent to write about the "Great War" in a comic vein; in fact, it undoubtedly is. But there is no reason that war should be regarded with reverence, and, as Fussell points out, perhaps humor is the only way to come to grips with the horror.

Graves' own approach to Good-bye to All That is perhaps summed up by his comment on life after the War:

I still had the Army habit of commandeering anything of uncertain ownership that I found lying about; also a difficulty in telling the truth — it was always easier for me now, when charged with any fault, to lie my way out in Army style.

Graves, Good-bye to All That 287 (Anchor 1985). These are lies in pursuit of a larger truth (as Fussell also points out). Even for someone with the good luck and mental toughness to survive the horrors of the trenches, it must be hard to look back into the abyss straight on. Sometimes, mockery is the only antidote to madness. Sitting here on a Sunday morning in my bathrobe at the keyboard with a cup of strong coffee, it is easy to contemplate the sucking, shell churned mud of half-frozen ditches, swarming with rats, amidst the heavy whine and thud of the shells, the moans and shrieks of the wounded in no-man's land, the ever present fear of gas, and the fatal knowledge that sooner or later one would be ordered to march straight on with bayonet fixed into the stuttering maw of a machine gun. Perhaps not quite so easy to contemplate for one who has lived the experience — a possible explanation for the taciturnity of so many old soldiers.

P.S. As a bonus, for anyone who has ever taught English as a Second Language abroad, see Graves' penultimate chapter on his assignment to Egypt as a professor.

Eat, Drink, and be . . .

Blue Plate Special: An Autobiography of My Appetites by Kate Christensen

Blue Plate Special: An Autobiography of My Appetites by Kate Christensen

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This book is not so much about the love of food as it is about using food to fill the absence of love. As Tolstoy pointed out, every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, and that certainly holds true in this fascinating and engaging memoir. Christensen chronicles a series of dysfunctional relationships, from her abusive father to her incompatible lovers, awash in a sea of alcohol and punctuated by bouts of depression. At times, the book seems like an extended therapy session. Christensen, however, not surprisingly, is perceptive, funny, and a trifle acerbic. It is not hard to believe that she is yet another successful novelist with a messy personal life. And for all that food is a proxy for love, the recipes are mouth watering. If only life were as straightforward as cooking.

View all my reviews

The Killer Angels

The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara

The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, of whom you may never have heard unless you are a student of the Civil War, was one of the pivotal figures at the Battle of Gettysburg, playing a key role in twice repulsing determined Southern assaults. He is also the most fully realized character in Michael Shaara's Killer Angels, whether he is agonizing over putting his brother in harm's way, coaxing a regiment of deserters back into action, or tending to his men while an old friend dies awaiting the surgeon's knife. But although Chamberlain plays a key role, the action is ultimately dominated by General James Longstreet and the legendary Robert E. Lee.

For this story is as much the story of the failure of the South as of the triumph of the North. And, like Tolstoy's Borodino or Hugo's Waterloo, the real protagonist is the battle itself, from the initial skirmishes at Cemetery Hill to the desperate defense of Little Round Top to the final awful and appalling calamity of Pickett's Charge. Shaara's story is compelling not so much because of the development of his characters, which is deft but not remarkable, but because he gives a thorough and lucid account of what happened during the battle and why, including the ultimate folly of hurling the infantry across an open field against fortified artillery on high ground. Shaara, himself a soldier, muses in the epilogue over why the lessons of Gettysburg seem not to have been learned by European generals in the twentieth century.

I strongly recommend this book not so much as high art but as living history, a crucial explication of one of the most significant events in American history, whose repercussions are felt to the present day.

View all my reviews

The French and the Russians

Just as when I read Wilde for the first time, I immediately thought, "This is Shaw;" upon reading the description of Waterloo today in Victor Hugo's Les Miserables, I thought, "This is Tolstoy!" And, indeed, I suppose it would be an interesting project to attempt to untangle the relationship between nineteenth-century French writers and their contemporaries in Russia.

Sleep That Knits Up the Raveled Sleeve of Care

Gretchen Rubin has seven tips on getting to bed on time and double that number for getting a good night's rest.

No Brainer

You Are Not So Smart: Why You Have Too Many Friends on Facebook, Why Your Memory Is Mostly Fiction, and 46 Other Ways You're Deluding Yourself by David McRaney

You Are Not So Smart: Why You Have Too Many Friends on Facebook, Why Your Memory Is Mostly Fiction, and 46 Other Ways You're Deluding Yourself by David McRaney

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

We live with the assumption that our conscious mind is finely tuned to perform rational calculation based on accurate perception and near-perfect recall. In fact, it is more akin to an evolutionary afterthought that operates on dubious premises, fuzzy memories, and irrational impulses. We are finely tuned to survive in a world where we may be someone's next meal, but the very behavior that may be adaptive under those circumstances may be unforeseen, unnoticed, or ignored in today's world, with consequences that range from the comical to the tragic.

McRaney offers a series of tart essays, each of which illustrates a quirk of the human mind that may be familiar to clinical psychologists but a revelation to the rest of us. If, like the ancient Greeks, one seeks to know oneself, this is an excellent place to start.

View all my reviews

Agility and Accomplishment

Getting Results the Agile Way: A Personal Results System for Work and Life by J.D. Meier

Getting Results the Agile Way: A Personal Results System for Work and Life by J.D. Meier

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

My best friend is a person who is, to all appearances, effortlessly organized. When we were roommates in college, he was up early, finished his homework in a demanding scientific discipline (while studying Chinese on the side) before dinner, and went to bed promptly by 9:00 p.m. after a leisurely dinner and a couple of hours of science fiction. This book is not for him.

Being the opposite of my best friend on the organizational scale, much of my life has been spent on a journey to bring life into focus and clean up my act. I am a modest, but not obsessive, consumer of organizational self-help books, from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's Flow to David Allen's Getting Things Done to Gretchen Rubin's Happiness Project.

J.D. Meier's Getting Results the Agile Way, based on his experience as a program manager at Microsoft, strikes me as a thoughtful and important contribution to the genre. Meier does not despise the minutiae of task management, but he attempts to transcend it. His emphasis is on identifying measurable goals, working toward them systematically, and evaluating the results regularly. In addition, he emphasizes the importance of recognizing that time and energy are finite resources, and he writes at some length about both effectiveness — doing the right things — and efficiency — doing them well.

Part of being both effective and efficient is boundaries and balance. If you work to exhaustion, it affects your ability to perform in every other area of your life. If you do not get at least a minimum amount of sleep, you won't function effectively. If you do not have some fun, your motivation will plummet. And if you do not pay attention to your relationships with other people, they will atrophy. While these observations may seem obvious, it nevertheless takes a certain amount of planning and discipline to ensure that people schedule a ceiling to the amount of time spent at work and a floor to the amount of time spent for fun, sleep, and other people.

Beyond his emphasis on the importance of short and long term goal setting, Meier is also an astute observer of the self-defeating mind games that prevent people from working effectively toward their goals, and he breaks down a number of simple strategies for addressing them, from settling for something less than perfection on a first iteration to plunging into work to escape analysis paralysis.

In all, Meier's book achieves what should be the goal of every good organizational book: it does not settle for tidying our schedules, but insists that we examine our goals in the hope that we will choose to live more meaningful lives.

View all my reviews

Farewell to Barnes & Noble

I made my last trip yesterday to what used to be our local Barnes & Noble bookstore. There was still a small cluster of fiction, war history, foreign language and diet books in the center of the store, along with some bestsellers on display. But the front of the store had been taken over by a simulacrum of an Apple Store pushing the "Nook," and the rest of the store seemed largely devoted to toys for small children. Even the music section had been gutted and turned over to video sales. The incredible shrinking book selection is so limited that it no longer presents a credible alternative to shopping on line. My prediction: within five years, Barnes and Noble, if it exists, will be a virtual operation: the brick and mortar stores will have gone the way of Borders.

Love and Glory: Last of the Lymond Chronicles

Checkmate by Dorothy Dunnett

Checkmate by Dorothy Dunnett

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

It is not often that the final course of a six course meal is as satisfying as the first, but Dorothy Dunnett serves up a banquet in the Lymond Chronicles that pleases more with every volume.

The violence of the sixteenth century court and battlefield sometimes reaches almost cartoonish levels, and the level of intrigue is such that, did we not have a record of such (later) historical events as the Gunpowder Plot, it could hardly be credited. Nevertheless, the novels are beautifully paced and plotted, and Dunnett weaves a rich tapestry depicting the pageantry, poetry, music, literature, and science of the era immediately preceding the cultural explosion of Elizabeth's reign. Indeed, while the novels deal principally with France and Scotland, looming in the background throughout is the rise of English greatness following the ascent of her most illustrious monarch.

To borrow a phrase from As Time Goes By, in the end, it's "the same old story, a tale of love and glory." But what a tale, and how beautifully told!

View all my reviews

Scotland's James Bond in the 16th Century

The Game of Kings by Dorothy Dunnett

The Game of Kings by Dorothy Dunnett

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

When Sir Walter Scott invented the historical novel in 1814 with the publication of Waverley, he took Europe by storm. As Georg Lukacs later pointed out, Scott also pioneered the technique of introducing a mediocre fictional character in the midst of the great actors on the historical stage, and used his protagonist to organize the action against the backdrop of major historical events.

Scott's technique has endured, but with the modification in modern historical fiction that the protagonist has become progressively less mediocre and progressively more superhuman. This is evident in such characters as Stephen Maturin in Patrick O'Brian's well-regarded series of nautical novels, and it is apparent in Francis Crawford of Lymond in the Game of Kings, the first book of Dorothy Dunnett's Lymond Chronicles. In other words, despite the apparent scrupulous historical accuracy of the novel regarding larger historical events, this novel has to be taken with a whopping suspension of disbelief.

However, if one can master one's disbelief, it is quite easy to seduced by Lymond, the master wit, clever polyglot, indomitable swordsman, incomparable strategist, and irresistible ladies man, whose self deprecating wit, charm, and occasional misstep render him engaging rather than obnoxious.

Moreover, the story is cleverly and tightly plotted, revealing a fascinating complexity but never revealing so much that one is not drawn to turn the next page. A bonus for those with an interest in the history of Scotland is the rich political interplay between the Scots and their larger and more powerful neighbors, England and France, during the infancy of Mary Queen of Scots.

In returning to the historical Scotland that gave birth to the historical novel, Dorothy Dunnett proves herself worthy of her great progenitor.

Scotland the Brave

Scotland: The Story of a Nation by Magnus Magnusson

Scotland: The Story of a Nation by Magnus Magnusson

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

My ancestry does not include much in the way of ethnic color, but the Scots provide most of what there is. Indeed, in the past century the Scottish branch of the family, at some remove, has included a fighter pilot and war hero, a celebrated poet, and two successful movie stars. So it's with a nod to our Caledonian ancestors that we toast each other on the holidays, and I seized on the opportunity to take my bride to Scotland when I got married.

So it was with some surprise that I discovered that, despite Scotland's disproportionate contribution to the modern world, it is not particularly easy to find a good general history of Scotland. Fortunately, Magnus Magnusson's engaging history of Scotland from its early history through the Act of Union makes up in verve what it lacks in sophistication. It vividly recounts the intrigues, murders, and battles of the Royal Court throughout the Stewart Dynasty, explores in some detail the history of the Covenanters and of Cromwell, and limns the portraits of a number of colorful figures in Scottish history such as Viscount Dundee, Rob Roy MacGregor, and Sir Walter Scott. Indeed, the history is loosely structured around Scott's earlier history, Tales of a Grandfather.

The popular tone of the work is often emphasized by a certain guidebook quality, as Magnusson points out the location of current monuments and motor routes, but ultimately this does little to detract from the narrative. At the same time, while the book does give a good general overview of the political forces at work in Scotland, which spent a great deal of time trying to play the French off against the English, one might need to look elsewhere for a theoretical explication of the progress of Scottish history.

In addition, except for a brief coda on the new Scottish parliament, the book effectively ends with the Act of Union and does not address the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth century history of the Scottish people after Scotland was no longer an independent country. While it is not really fair to criticize a book for not doing what it doesn't intend to do, it seems a shame in some ways that this very rich and often turbulent era in the history of the Scottish people is not addressed.

Stereotyping Our Sisters

Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America by Melissa V. Harris-Perry

Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America by Melissa V. Harris-Perry

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I picked up Sister Citizen because I am interested from a legal perspective in the implications that stereotyping of African American women has in the workplace. The book more than rewarded my interest.

The book is a pastiche of literary excerpts, critical essays, news analysis, focus group reporting, and statistical surveys that covers everything from the writings of Zora Neale Hurston and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina to the success of Michelle Obama and the shaming of Shirley Sherrod. In between it packs powerful statistical analyses of the attitudes of African American women toward everything from themselves to God.

Unifying the work are several potent themes. One is the way in which the expectation that African American women will live up to the image of the "Strong Black Woman" is both a source of strength for African American women and an obstacle to full political involvement in the community. The obverse of self-reliance is inhibition about seeking help from others. A second is that the way in which women are treated is often determined by which of several stereotypes are imposed on them. A third is the way in which community solidarity can turn into community shame.

A particularly valuable contribution of Ms. Harris-Perry's opus is that not only does it reveal the results of introspection on the part of the women it studies, but it also reflects their attitudes toward the larger white community. As such, it shines a spotlight on some common ground between the two, but also reveals significant gulfs in understanding.

African American women occupy a unique place in the Black Community and in society at large. They are among our most vulnerable citizens both in terms of resources and negative stereotyping, At the same time, the word they used most often to describe themselves was "strong," and they are pillars of their families, churches, communities, and society at large. The aim of this book is to point the way toward their fuller integration into American society, both so that their contributions will be more fully realized and so that they can lay claim to the broad support of the society to which they contribute.

The Moral Blindness of Michele Bachmann

The most disturbing portion of Ryan Lizza's lengthy profile of Michele Bachmann comes almost at the end, when he describes her "must-read" list. Third on the list is a biography of Robert E. Lee by J. Steven Wilkins, which Lizza characterizes as a celebration of the godly antebellum South versus the godless abolitionist North. Admittedly, I have not personally read Mr. Wilkins' biography, but if Lizza is accurate, the book essentially echoes John C. Calhoun's argument that "slavery is a positive good" with a "Christian" twist. Lizza's article includes the following damning quotation:

Slavery, as it operated in the pervasively Christian society which was the old South, was not an adversarial relationship founded upon racial animosity. In fact, it bred on the whole, not contempt, but, over time, mutual respect. This produced a mutual esteem of the sort that always results when men give themselves to a common cause. The credit for this startling reality must go to the Christian faith. . . . The unity and companionship that existed between the races in the South prior to the war was the fruit of a common faith.

[Read more]

When Bachmann or Sarah Palin make such minor historical slips as confusing the birthplaces of John Wayne and John Wayne Gacy or claiming that Paul Revere was warning the British, it simply makes one wonder whether they have a sufficient education and grasp of detail to lead their local Rotary Club, much less the United States. But espousing a "Christian" ideology that obliterates our country's central moral struggle with a "Big Lie" is a far more serious matter. This is not merely carelessness born of ignorance, it is indifference in the service of oppression.

The March to the Sea

The March by E.L. Doctorow

The March by E.L. Doctorow

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This brilliant but flawed work of historical fiction chronicles William Tecumseh Sherman's storied march to the sea and its aftermath until the end of the Civil War. The book is brilliant in its insight but flawed by an almost Dickensian sentimentality at times; for example, the noble African American photographer Calvin Harper is afflicted by blindness after he tries to foil an assassination attempt. Although there is death aplenty in this story, the way it is meted out suggests a poetic justice that seems out of place in a modern novel about war, where death takes both the just and the unjust indiscriminately.

The novel does convey admirably however the sense in which the fairy tale life of the Southern planters was sustained by an engine of terrible cruelty and oppression, along with Sherman's sense that the only way to end the War the South had started was to irrevocably smash not only its means for making war but the ties that held the society together. In the wake of the maelstrom that was Sherman's march, neither person, property, nor place survived. Those who were not killed were bereft; it was not so much that they lost their place in society, but that they lost the society in which they had formerly held a place.

The liberation of the slaves was of course an equally important part of the attempt to eradicate the South's institution of oppression, but it seems here to have been carried out with little forethought. Former slaves followed the Army in large numbers, while the Army was constantly trying to shake them off. Some of Doctorow's best writing deals with sentiments of the former slaves and their struggle to find a place for themselves in the postwar wasteland. They were free, for the moment, but they were also on their own.

Good Books and Last Meals (Well Read and Well Fed)

I suppose that I am like many other people in that as I get older, I read fewer books, choose them more carefully, and finish a smaller number. Youth has the luxury of reading indiscriminately and the opportunity to do so. As one gets older, there is not only less time to read, but there will be less time to enjoy what one has read. So one might as well choose carefully, because the universe of books that one could profitably read will always dwarf the number of books one actually can read.

If I am granted free choice of my last meal, it will be a sushi starter, harira, lobster and caviar, filet and foie gras, artichokes, mechoui, tajine dial djej ma zaitoun, and creme brulee, washed down with good red wine, followed by mint tea, espresso, and laphroaig.

NOT a cold glass of wheat grass juice.

I aspire to a literary banquet just as rich and varied.

Eat Fat to Get Thin

Good Calories, Bad Calories by Gary Taubes

Good Calories, Bad Calories by Gary Taubes

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

My new motto is "145 by July," meaning I would like to trim 50 pounds of fat accumulated over 20 years in approximately six months. In the process, I am hoping to see a reduction in my blood pressure and the level of triglycerides in my bloodstream to a more acceptable level. For anyone who subscribes to the conventional wisdom about dieting, this is a truly Quixotic aspiration.

Gary Taubes, in Good Calories, Bad Calories, attempts to turn the conventional wisdom on its a head. A historian of science and a writer for Science magazine, Taubes argues trenchantly that the fundamental assumptions driving popular wisdom about diet in the United States are based on bad science, and that the studies necessary to draw truly scientific conclusions about diet have not been performed.

Taubes assails the notion that every extra calorie consumed adds to the bulge on the waistline, and that the only way to lose weight is semi-starvation. Rather, he suggests, the root of our modern obesity epidemic is more likely to be found in our consumption of refined grains, refined sugar, and high fructose corn syrup, all of which are comparatively recent phenomena in evolutionary terms.

Taubes posits that weight gain has more to do with hormonal regulation of energy storage than with the simple addition of calories. In simple terms, heavy carbohydrate consumption causes an insulin rush that halts the body's use of fat for energy and encourages the conversion of glucose into fat, which both contributes to weight gain and encourages overconsumption.

Taubes' response is to encourage a high fat, low carbohydrate diet. To critics who suggest that such an approach is fraught with peril in that it increases the risk of heart disease, Taubes argues that the best science suggests that the risk of heart disease has far more to do with being overweight than with the consumption of fat or cholesterol. And, he argues, being overweight has more to do with carbohydrate consumption than fat consumption.

In one sense, Gary Taubes is the Robert Caro of diet writers. His book is so thoroughly researched, tightly written, and copiously annotated that it hard for a layman to contest his assertions. If you find a better explanation of the origin of obesity and effective strategies to counter it, read it.

The Perversion of Adam Smith

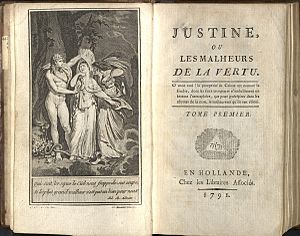

Image via Wikipedia

The name of Donatien Alphonse Francois, Marquis de Sade, has unfortunately been reduced in modern times to a cliche for a sexual kink. Spinning out his fantasies of sex and power, mostly from within prison walls, as France's corrupt ancien regime crumbled, de Sade had a clear-eyed view of the implications of the pursuit of self-gratification without restraint; not only did he see it, but he exalted it into a philosophy.

Dipping into Justine on my subway ride into work, I am continually struck by the elegance and simplicity of the creed of le bon Marquis. It might be crudely rendered, "Good guys finish last," but that would be incomplete. The Marquis spells out the full implications of that little phrase, and maybe his spirit is better captured in P.T. Barnum's credo, "Never give a sucker an even break." For de Sade, this is not merely a maxim, but a principle. Not only do the strong oppress the weak in de Sade's writings, but the strong should oppress the weak. To do otherwise would be frankly irrational.

The weak are not wholly helpless, of course. They can volunteer as the minions of their oppressors in the hopes that they will be spared so long as they are useful or entertaining. And even strong personalities need allies; so prudential considerations sometimes temporarily restrain the impulse to dominate and exploit. Or, finally, the weak can resort to crime:

"Think it over, my child, and understand that nature has placed us in a situation where evil is necessary, and that she gives us at the same time the means to employ it, so that evil obeys its own laws just as good does, and natures gains as much from one as the other; we were created equal, but what changes this equality is no more culpable than what seeks to reestablish it."

Justine, 467 (my translation).

De Sade was a contemporary of Adam Smith and Immanuel Kant. In a way, de Sade is a bit like Smith with the gloves taken off. Smith postulated a world of perfect competition in which the invisible hand of the marketplace would regulate men's affairs as each person pursued his own self-interest. De Sade turns Smith's orderly marketplace into a carnival in which self-interest runs amok. The invisible hand does not cease to order the mechanism of society, but the social consequences are poisonous. De Sade has a clear-eyed view of the real consequences of unrestrained self-interest, in which the strong prosper and the weak go to the wall, and he glories in it. De Sade sees people prosper by rapine and murder, so he concludes that this is the natural order, and "virtue" but a fantasy of the weak or a deceit of the strong. In his lawless dystopia, everyone is free and no one is safe; self-interest reigns supreme, and we are once again microbes brewing in Jack London's "yeasty ferment." De Sade is the anti-Kant: Kant cautioned that people should always be viewed as ends rather than means; de Sade retorts the people should always be exploited as means rather than ends, and that Smith and Kant are sentimental ninnies.

Image via Wikipedia

If those who forget history are doomed to repeat it, then perhaps the bankers and brokers of today's ancien regime should dust off the history books and remind themselves that the Place de la Concorde once went by a very different name. We teeter on the abyss, but we can save ourselves yet if only we take heed.