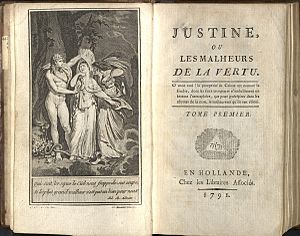

Image via Wikipedia

The name of Donatien Alphonse Francois, Marquis de Sade, has unfortunately been reduced in modern times to a cliche for a sexual kink. Spinning out his fantasies of sex and power, mostly from within prison walls, as France's corrupt ancien regime crumbled, de Sade had a clear-eyed view of the implications of the pursuit of self-gratification without restraint; not only did he see it, but he exalted it into a philosophy.

Dipping into Justine on my subway ride into work, I am continually struck by the elegance and simplicity of the creed of le bon Marquis. It might be crudely rendered, "Good guys finish last," but that would be incomplete. The Marquis spells out the full implications of that little phrase, and maybe his spirit is better captured in P.T. Barnum's credo, "Never give a sucker an even break." For de Sade, this is not merely a maxim, but a principle. Not only do the strong oppress the weak in de Sade's writings, but the strong should oppress the weak. To do otherwise would be frankly irrational.

The weak are not wholly helpless, of course. They can volunteer as the minions of their oppressors in the hopes that they will be spared so long as they are useful or entertaining. And even strong personalities need allies; so prudential considerations sometimes temporarily restrain the impulse to dominate and exploit. Or, finally, the weak can resort to crime:

"Think it over, my child, and understand that nature has placed us in a situation where evil is necessary, and that she gives us at the same time the means to employ it, so that evil obeys its own laws just as good does, and natures gains as much from one as the other; we were created equal, but what changes this equality is no more culpable than what seeks to reestablish it."

Justine, 467 (my translation).

De Sade was a contemporary of Adam Smith and Immanuel Kant. In a way, de Sade is a bit like Smith with the gloves taken off. Smith postulated a world of perfect competition in which the invisible hand of the marketplace would regulate men's affairs as each person pursued his own self-interest. De Sade turns Smith's orderly marketplace into a carnival in which self-interest runs amok. The invisible hand does not cease to order the mechanism of society, but the social consequences are poisonous. De Sade has a clear-eyed view of the real consequences of unrestrained self-interest, in which the strong prosper and the weak go to the wall, and he glories in it. De Sade sees people prosper by rapine and murder, so he concludes that this is the natural order, and "virtue" but a fantasy of the weak or a deceit of the strong. In his lawless dystopia, everyone is free and no one is safe; self-interest reigns supreme, and we are once again microbes brewing in Jack London's "yeasty ferment." De Sade is the anti-Kant: Kant cautioned that people should always be viewed as ends rather than means; de Sade retorts the people should always be exploited as means rather than ends, and that Smith and Kant are sentimental ninnies.

Image via Wikipedia

If those who forget history are doomed to repeat it, then perhaps the bankers and brokers of today's ancien regime should dust off the history books and remind themselves that the Place de la Concorde once went by a very different name. We teeter on the abyss, but we can save ourselves yet if only we take heed.